Review Article

Review Article

Neurocysticercosis and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Correlations -Systemic Review and Case Report Article

Mariami Natsvlishvili1, Tinatin Chkhartishvili1, Aditi Pandey1, Harshal Praveen Singh1, Swapnil Ahuja1,Nadiya Konda1, Vishwajeet Dhananjay Dhane1, Maha Prathiksha Arul Essakkiraj1, Chetali Patil1,Riya Rahul Khedkar1, Asma noormohmed patel1, Rufiyat Mohsin Patel1, Mirza Khinikadze*2, Koka Gogichashvili2 and Mirzabayev Marat3

1School of Medicine, New Vision Univeristy, Georgia

2Caucasus medical centre, New vision University, Georgia

3Assistant of the Department of Neurosurgery KazNMU named after S.D. Asfendiyarov, Kazakhstan

Mirza Khinikadze (M.D, Ph. D), Caucasus Medical Centre, New Vision University, Georgia.

Received Date:August 09, 2022; Published Date: August 26,2022

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is the most common helminthic infection of central nervous system (CNS) that causes an ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebrovascular complication. Most often causative agent is larval form of the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium, leading the development of cysts in the brain. Cerebrovascular manifestations in NCC are a result of vasculitis, which is a complication of subarachnoid cysticercosis due to an inflammation of small-sized or medium-sized wall arteries (arteritis) or veins (phlebitis), which occurs in 2-15% cases and has variable responses in intensity of an inflammatory response, that is not related to the intensity of changes in the vessel wall. This review article analyzes correlations that might exist between subarachnoid neurocysticercosis and an infectious intracranial aneurysm and introduces one interesting case regarding that topic which was found by above mentioned authors.

Keywords:Neurocysticercosis; Subarachnoid hemorrhage; Taenia solium; Intracranial aneurysm; Cerebrovascular; Infectious vasculitis

Abbreviations:NCC-Neurocysticercosis; SAH-Subarachnoid Hemorrhage; CNS-Central Nervous System; NCBI-National Center Of Biotechnology Information; ADPKD-Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease; CT Scan-Computer Tomography Scan; CTA-Computer Tomography Angiography; ASAHNCC - Aneurysmal SAH Associated To Neurocysticercosis; LACA-Left Anterior Communicating Artery; MRI-Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CSF-Cerebrospinal Fluid; IL-Interleukin; TNF-Tumor Necrosis Factor; IFN-Interferon; Ige-Immunoglobulin E; Rcts-Randomized Clinical Trials

Introduction

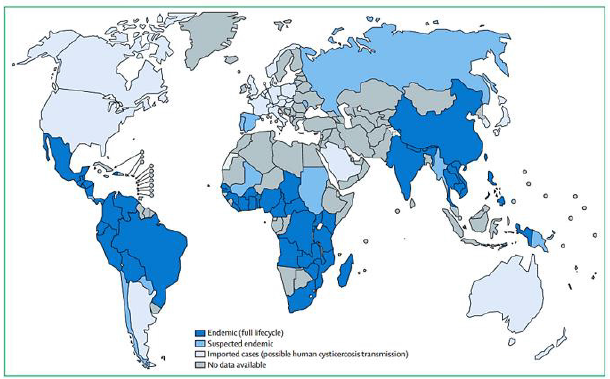

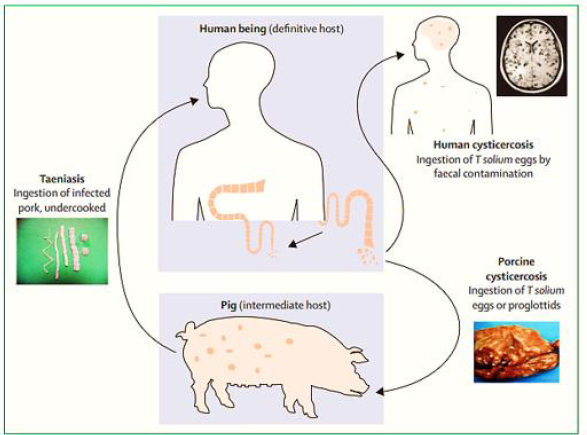

Neurocysticercosis is an infection of CNS caused by pork tapeworm Taenia Solium which belongs to the Cycliphyllid Cestode family Teaniidae. The life cycle of the T. Solium requires two mammalian hosts - a definitive host which is human and an intermediate host which is pork. The tapeworm attaches to an intestinal wall with the help of a head called Scolex which has suckers and hooklets. Larva cysts or eggs of the T. Solium can be transmitted to humans by two ways. First way of transmission is when intermediate host ingests eggs from food and water which is contaminated with human feces, it attaches to the gut wall, follows the bloodstream, and reaches different organs. Another and the most common way of transmission is ingestion Larval cysts, called cysticerci, from undercooked pork. It is worth mentioning that a tapeworm is endemic in low-income countries, especially where the pigs’ farms are common-Latin American countries, sub-Saharan Africa, and large regions of Asia, including the Indian subcontinent, most of southeast Asia, and China. However, increased immigration and tourism has lengthened the dissemination.

T. Solium causes the deposition of cysts called cysticerci and as a result, causes infection. Cysticerci can be found in any organ (muscle, heart, skin) but the most serious manifestation is the encystment of the brain - Neurocysticercosis. Neural symptoms depend on the location and the size of the cyst. It can cause increased intracranial pressure and adult-onset epilepsy. Some research show that subarachnoid hemorrhage is also associated with extraparenchymal NCC. Let’s briefly discuss some information about subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). SAH is bleeding in the space between human brain and the surrounding membrane (subarachnoid space). The primary symptom is a sudden, severe headache. The headache is sometimes associated with nausea, vomiting and a brief loss of consciousness.

Bleeding usually results from the rupture of an abnormal bulge in a blood vessel (aneurysm) in the brain. Sometimes bleeding is caused by trauma, an abnormal entanglement of blood vessels in patient’s brain (arteriovenous malformation), or other blood vessel or health problems (Figure 1 & 2).

Figure 1:Geographical prevalence of Taenia solium Reproduced from the First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases [10] by permission of the World of the Health Organization.

Figure 2:Lifecycle of Taenia solium Reproduces and adapted from Garcia and colleagues [16].

The most common causes are smoking, high blood pressure, excessive alcohol consumption, a family history of this condition, severe head injury, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Most of the brain aneurysms won’t rupture but a procedure to prevent subarachnoid hemorrhages is sometimes recommended if they’re detected early.

Computerized tomography (CT scan) of the brain is a simple and effective way to see a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Another type of CT scan, CT angiography (CTA), visualizes blood vessels using a contrast material injected intravenously (through a vein). There are several ways to treat a brain aneurysm, including open surgery or endovascular treatment. Endovascular treatment of an aneurysm is a minimally invasive procedure using cerebral angiography to access the aneurysm. The decision about what treatment is the best, depends on the characteristics of the aneurysm and overall health condition of the patient. Open surgical techniques include clipping or bypass, endovascular surgical techniques options are coiling and/or stenting/flow diversion.

Materials and Methods

We worked as per the norms given in the PRISMA 2020 checklist. The purpose of this paper is to expound the accompanying case and to correlate the different known pathologies with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Eligibility Criteria

Our qualification measures comprise patients separated by the demographics as well as risk factors and other comorbidities present. While working on our case, and furthermore subsequent to keeping an eye on various papers we saw that articles containing a couple of factors that had to be excluded from our pursuit, and simultaneously, we settled on something worth agreeing which is referenced in the consideration rules below. Finding correlation between NCC and Sub-arachnoid hemorrhage was our main goal of this study.

Inclusion Criteria

Individuals from endemic regions like Latin America, India,

Africa and China.

• Immigrant individuals from above mentioned countries in the

developed countries.

• Young and middle-aged patients.

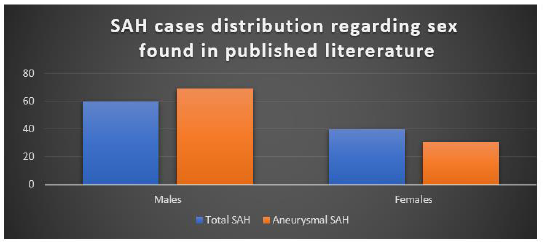

These criteria were followed throughout the work by the commentators and all the papers comprehensive of individuals related to NCC from endemic regions and patients with a history of immigration were incorporated. Likewise, explicit work was done from the given data across all the papers to guarantee that most of the patients were young and middle-aged. Many cases were studied from 1980-2012 and text reported in English has been considered for data extraction and review. A sum of 20 cases of SAH associated with NCC was found in the published literature (twelve of them corresponded to ASAHNCC) and the Male sex was predominant: 60% for total cases of SAH; and 69.2% for aneurysmal SAH (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

In July 2022, through literature review, a systematic search of Pubmed, NCBI, Google Scholar, and Medline databases was conducted using the keywords- neurocysticercosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, hemorrhagic cerebrovascular event, aneurysm, and stroke. All the articles searched through these databases were again reviewed to meet our eligibility criteria.

Exclusion Criteria

• All patients with known history of cardiovascular risk factors or other comorbidities such as hypertension, etc. Cerebrovascular disease associated with NCC predominantly involves small vessels.

While surveying, we excluded any papers containing individuals with known history of cardiovascular risk factors or other comorbidities to avoid any conflict in our study. Patients diagnosed with NCC and associating comorbidities such as hypertension, familial hypercholesterolemia and predisposed risk of having aneurysm were excluded. Over 50% of patients with subarachnoid NCC have angiographic evidence of vasculitis

Information Sources

During our search, the commentators used Pubmed, NCBI, Google Scholar, and Medline databases and filtered all the research articles, case reports, and systematic surveys. This systemic search was carried out with the keywords mentioned above in the inclusion criteria. The search consisted of finding published articles, and abstracts in the English language from 1980-2012.

Search Strategy and Selection Process

Our search strategy was principally focused on finding as many articles as we could find pertaining to the Neurocysticercosis and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Selection process and data collection process

Synthesis Methods

In July 2022, we made literature review of above mentioned databases and keywords using. The purpose of this paper is to expound the accompanying case and to correlate the different known pathologies with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

According to Edinson Dante Meregildo Rodriguez’s literature review, The aetiopathogenesis of strokes in NCC comprises the following mechanisms: thrombosis of penetrating and small superficial cortical vessels in the brain base caused by arteriopathy - the most frequent mechanism -; occlusive endarteritis caused by thickening of the adventitious layer of small perforating arteries; focal arteritis with endothelial hyperplasia; medial fibrosis due to local inflammation and inflammatory aneurysms.

Cerebrovascular disease associated with NCC transcendently includes small vessels. More than half of patients with subarachnoid NCC have angiographic evidence of vasculitis. In some patients, the only vascular finding in neuroimaging studies was the presence of a fusiform aneurysm located in the left anterior communicating artery (LACA). There are no demonstrative criteria for aneurysmal SAH associated with neurocysticercosis (ASAHNCC). The diagnosis of ASAHNCC is usually made upon the synchronous conjunction of both diseases.

From a public health perspective, this case is very instructive mainly for two reasons. Firstly, NCC is a little-known etiology of stroke, even in endemic nations. Secondly, this case could serve as a pertinent reminder that although NCC is uncommon in evolved nations, this could turn into a more normal sickness in view of the rising pattern of migration. Subsequently, clinicians in these nations should be aware of NCC and its complications. Therefore, NCC should be included in the differential diagnosis of aetiologies of stroke, especially in young and middle-aged adults, and in residents in or migrants coming from cysticercosis endemic nations.

Results

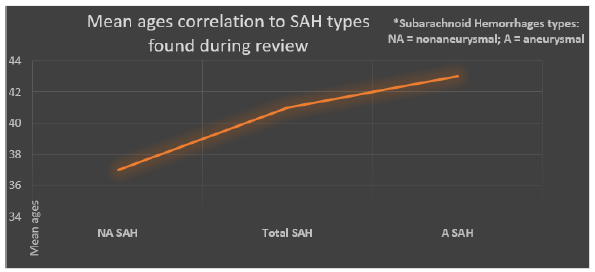

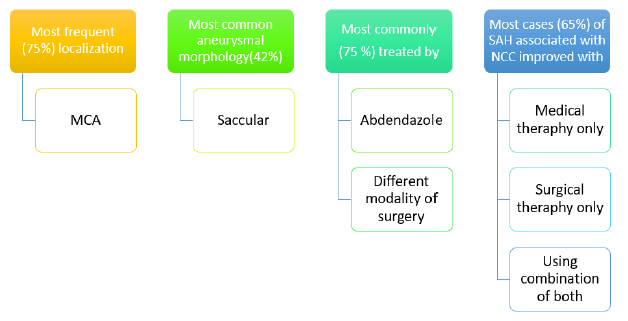

Until this point in time, a sum of 20 cases of SAH associated with NCC was found in the published literature (twelve of them corresponded to ASAHNCC). The mean age was 41 years for total cases of SAH; 43.2 years for aneurysmal SAH; and 37.5 years for non-aneurysmal SAH. Male sex was predominant: 60% for total cases of SAH; and 69.2% for aneurysmal SAH. Among patients with aneurysmal SAH, the most frequent (75%) aneurysmal localization was MCA, 75% were treated with albendazole and any modality of surgery; the most common (42%) aneurysmal morphology was saccular. Most cases (65%) of SAH associated with NCC improved (75% among cases of aneurysmal SAH) with medical and/or surgical therapy (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

The relation between NCC and stroke is deeply grounded. It has been accounted that NCC is associated with ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, including aneurysmal and non-aneurysmal SAH. NCC accounts for 4%-12% of stroke cases. However, in cysticercosis-endemic regions, according to the study by Alarcon et al., NCC can be the etiology of more than 10% of strokes. 10- 20% of patients with neurocysticercosis develop communicating hydrocephalus due to inflammation and fibrosis of the arachnoid villi or inflammatory reaction to the meninges and ensuing impediment of the foramina of Luschka and Magendie (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

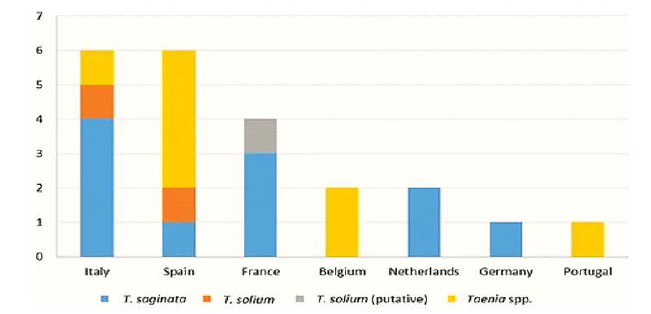

Cases of taeniosis have been discovered in 12 of the 18 Western European countries. Cases have not been documented in Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. For Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the UK, annual cases of taeniosis have been reported and the number of cases detected annually ranged between 1 to 144. Prevalence detected varied from 0.05% to 0.27%, while estimated prevalence varied from 0.02% to 0.67%. The majority of taenia cases have been reported as Taenia spp. or T. saginata, though T. solium has been recorded in Denmark, France, Italy, Spain, Slovenia, Portugal and UK. Cases of human cysticercosis have been reported in all countries of Western Europe, with the exception of Iceland, where the greatest number came from Portugal and Spain. Most cases of human cysticercosis were suspected of being infected outside Western Europe. Cases of T. solium have been observed in pigs in Austria and Portugal, although only the two cases in Portugal have been confirmed by molecular methods. Germany, Spain and Slovenia have reported porcine cysticercosis but have not made a distinction between Taenia species. Bovine cysticercosis was detected in all countries, except for Iceland, with a prevalence based on meat inspection of between 0.0002 and 7.82% (Figure 6).

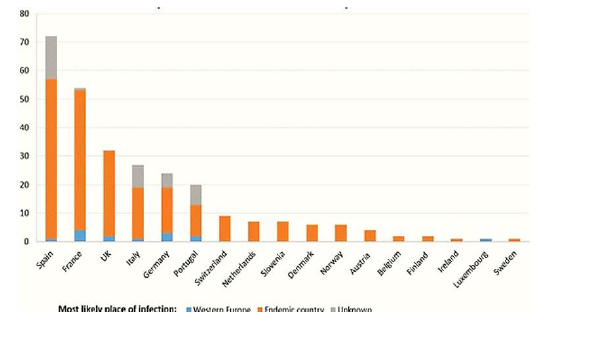

Overall, 275 cases of cysticercosis have been reported in 17 countries. No cases were detailed from Iceland. Spain (72 cases) and France (54 cases) enlisted the foremost cases. The typical number of cases reported per annum was 10.6, 2014 being the year within which the quantity of cases was highest (25) and 1997 the year

within which the number of cases was lowest among all 17 countries. Quiet age extended from 2 to 94 years. 129 were female and 127 were male (19 cases of obscure sexual orientation) (Figure 7).

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

In most cases, risk factor information was reported. In 82% of cases, infection was probably acquired outside of Western Europe (61% immigrants, 21% traveling or staying in endemic areas). Among contaminated vagrants, most cases moved from Latin America (77), taken after by Asia (39) and Africa (35), and 15 cases in Eastern Europe (e.g. Albania, Bosnia, Herzegovina, previous Yugoslavia). In 5% of cases, disease showed up to have been obtained suddenly (no travel/movement history detailed). For the remaining cases (13%), there was no data on nationalities or hazard variables that can be related with the disease.

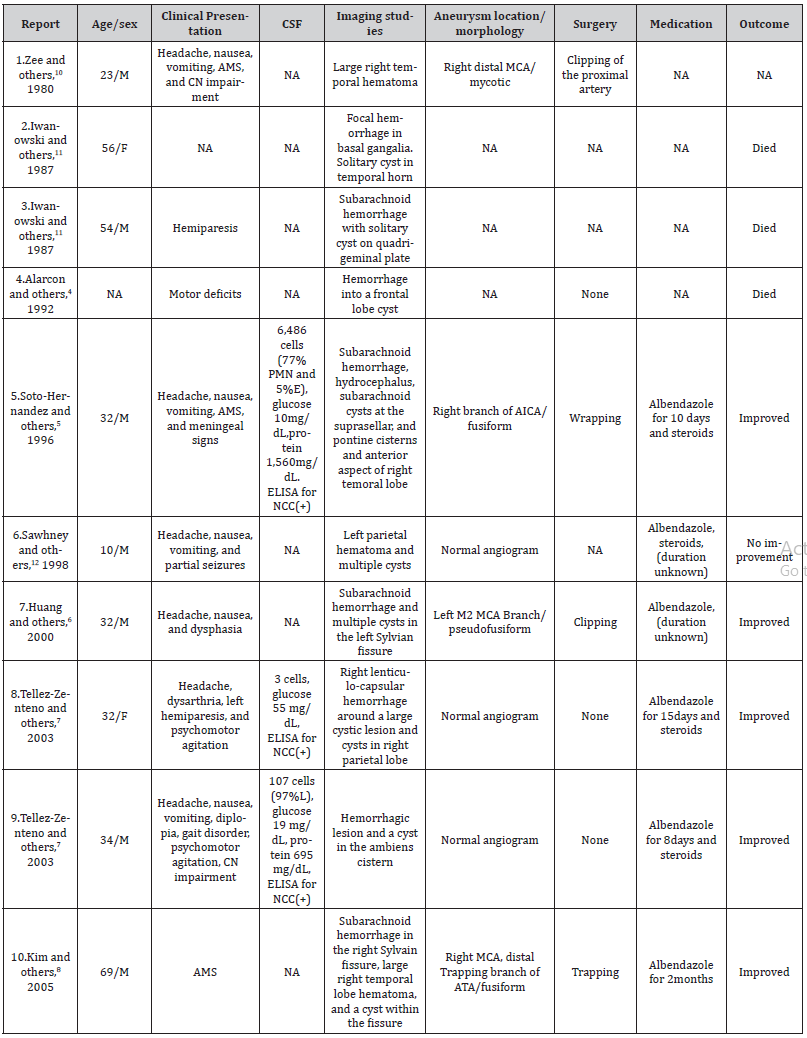

By survey of the writing, we too found out 10 other cases with aneurysmal or non-aneurysmal hemorrhagic cerebrovascular occasions related with neurocysticercosis within the writing. The cruel age was 38 a long time (middle: 33). Most cases were guys (70%, 7 of 10 cases; information was not accessible for one case). Four cases (36%) were found to have an aneurysmal hemorrhagic occasion. Four (36%) had negative cerebral angiograms and thus had a non-aneurysmal hemorrhagic event. Three (28%) did not report adequate data to classify them as aneurysmal or nonaneurysmal. Area of lesions was changed but maybe the foremost common introduction included subarachnoid hemorrhage within the Sylvian fissure (28%, 3 of 11 cases). All three patients who had an examination of cerebrospinal liquid (CSF) showed proof of anticysticercal antibodies within the CSF. All cases with aneurysmal hemorrhagic occasions experienced effective surgical repair of the aneurysms. Seven patients received albendazole (including three who had surgery) together with corticosteroids. Three patients died; all presented in the pre albendazole era. Below in Table 1.1 are ten cases of SAH related to NCC (Table 1).

Table 1:Cases of aneurysmal and non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with neurocysticercosis published to present.

Case Report Part

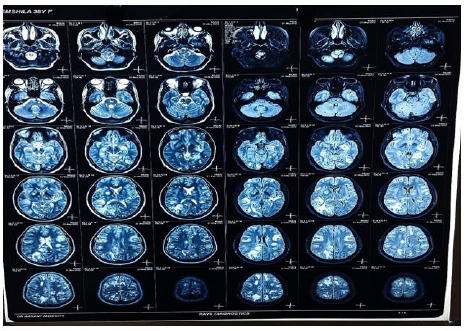

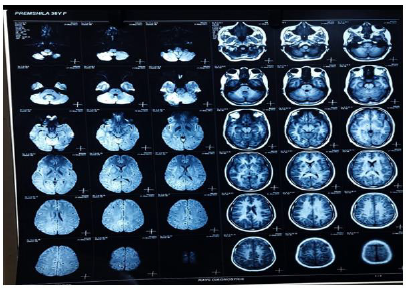

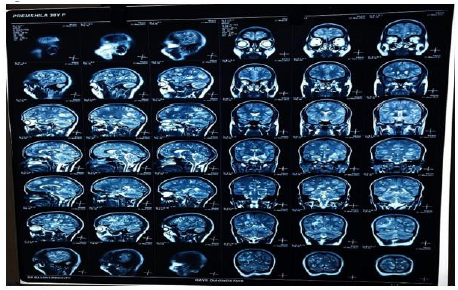

Regarding fact, that there is a rare case described and found associated topic of our review paper, we decided to analyze already existing papers and find correlation between SAH and NCC. But also, fortunately, we became able to describe to you interesting case, which we found a case in India of a 36-year-old female presented to a physician, with an intermittent history of headaches for the last 6 months followed by seizures, before admission, the headache suddenly became severe. During the physical examination, respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems were almost unremarkable. Past medical history was unremarkable. The patient had a habit of eating raw vegetables directly from the agricultural field and poor sanitation due to her low social-economic status. Routine laboratory analyses were normal. Western blot for cysticercosis for specific IgG and IgM was reactive. In Gadoliniumenhanced Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a typical starry sky appearance confirmed multiple active cystic lesions with central hyperintense content (scolex).

Treatment with mannitol 20% (2 ml/kg IV every 4 h), dexamethasone 0.1 mg/kg/d IV, fentanyl 50 μg/h IV, and nimodipine 30 mg PO every 4 h was initiated. This patient evolved favorably with 15 mg/ kg/d albendazole and corticosteroids (Figures 8,9,10).

Figure 8:

Figure 9:

Figure 10:

Figures 8,9,10 shows Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a typical starry sky appearance confirmed multiple active cystic lesions with central hyperintense content (scolex)

There are different neurological complications between person to person according to number, size, location, the stage of the cysts and the immune response of the host. As, in our case of NCC the patient had multiple active cystic lesions in left and right hemispheres (Figure 9). The left side was seen more affected. The number of many lesions can be due to the fact, that the patient was eating raw vegetables and was from a low socioeconomic status. So, she might not have seeked medical attention in the early stages of the disease which in turn led to epileptic seizures which can be seen as a common complication of NCC. The reason for the severe headache can be rising intracranial pressure or due to a ruptured aneurysm which must be confirmed by angiographic studies.

This case illustrates that the NCC should be viewed as a differential diagnosis of stroke for younger and middle-aged patients especially if they do not exhibit conventional cardiovascular risk factors and come from endemic areas for cysticercosis.

The burden of neurocysticercosis ranges from 90% to 95% daily per year, corresponding to 3.54 to 3.56 daily per 1000 population. Average yearly incidence rate per 1000 person-per year were 0.23 for NCC, 4.89 for epilepsy, 0.130 for status epilepticus, 0.62 for migraine headache and 1.02 for hydrocephalus. Most significant clusters were in southern regions of the highland of the country.

Discussion

Most of the research has concentrated on ischemic events, despite the fact that cerebral cysticercosis in particular, subarachnoid cysticercosis has been associated with the development of cerebrovascular events. The etiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage in neurocysticercosis remains unknown due to limitation on availability of causes related to it.

We discovered a case of NCC in India, where the patient received treatment with mannitol (20%) (2 ml/kg IV every 4 h), dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg/d IV), fentanyl (50 g/h IV), and nimodipine (30 mg PO every 4 h). With corticosteroids and albendazole at 15 mg/kg/d, this patient improved significantly. Though there were no documented complications of SAH caused by NCC.

We looked at a number of papers. There are limited cases of hemorrhagic presentation in the medical literature, and this is the main limitation in our study. A study found that people between the age of 75 and 84 had the highest frequency of unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Old women in particular are thought to be more vulnerable. The inflammatory response of the brain tissues to the infection of NCC can be associated with aneurysm reports in young children or people who have a history of infection with Taenia Solium. Mostly brought on by high levels of inflammatory cytokines such 1L, IL-10, TNF, IFN gamma, IgE, and IL-4 in patients who have a history of consuming pork and raw vegetables directly from farm. Aneurysm formation results from the artery wall becoming weakened by the severe inflammatory response, invading tiny arteries, and degenerating cysts. Leptomeninges may thicken as a result of an inflammatory exudate that the subarachnoid cysts may produce. According to an article, the inflammatory reaction further sparked by the exudate can lead to endarteritis and endothelial hyperplasia, which can further aid in the development of aneurysms. When a blood vessel bursts due to an inflammatory aneurysm, a degenerating cyst in a small vessel, or other clearly inflammatory processes of a small penetrating artery, it might result in a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Treatment Plan

Patients having both living and degenerative/dead parasites may require separate treatments. In patients with cystic parenchymal NCC the use of anthelmintic and corticosteroids are preferred and there are sufficient studies on it as well. Currently, many randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on drug therapy are working on establishing the comparisons on various combinations of drug therapy like use of anthelmintics therapy alone or corticosteroid therapy alone or combination of both. Although, study of several different regimens at once has never been done.

Conservative therapy

The initial management involves symptomatic treatment if the patient has seizures and/or hydrocephalus.

Pharmacologic therapy

Albendazole high doses (30mg/kg/day), alone or in combination with praziquantel (50-100mg/kg/day) with corticosteroids (intravenous dexamethasone 24 mg/day followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day) are successful plans but it is not a recommended approach for solitary parenchymal cyst and recurrent seizures. Anti-epileptic drugs administered for the patient with seizures till the lesion resolves and then must be stopped. If the patient still has seizures anti-epileptic drugs must be continued. Cimetidine is also started to bypass first pass metabolism.

Surgical therapy

For the aneurysmal events associated with NCC surgical therapy is the preferred method which involves the mechanical removal of the cysts, reducing inflammation and obstruction of CSF pathways. The method (clipping, trapping and bypass) depends on the location. If the patient has hydrocephalus emergent placement of ventriculostomy/cystectomy alone. For obstructive cases minimally invasive surgery is indicated. The high risk of shunt failure can be minimized by antiparasitic drugs and corticosteroids.

Post operative therapy

Cysticidal drugs are given in all cases for a week along with prednisone.

Role of corticosteroids in the treatment of NCC.

Corticosteroids are in use even before surgery or any specific therapeutic method was put in use. As of now, there are no records of randomized research trials that scrutinize the effectiveness of corticosteroids or ways to use them in other forms of NCC. Only the study related to solitary degenerating T.solium granulomas are available. Additionally, corticosteroids are frequently used to stop or reduce brain inflammation that occurs after anthelmintic treatment for parasite cysts with the cysticidal medications albendazole or praziquantel.

Within the first week of starting treatment with praziquantel, researchers saw the emergence of acute clinical symptoms/ signs like seizures, mass effect, and mortality. Treatment causes the normal stable, non-inflammatory host-parasite connection to break down through unknown processes, triggering an acute immune reaction against the parasite. These adverse effects were quickly determined to be attributable to inflammation and were successfully treated with corticosteroids.

Albendazole was introduced 2 years after praziquantel as another cysticidal drug but albendazole has its side effects too. In a double-blind trial that was previously published, the albendazole treatment group’s rate of generalized seizures increased in the first month after starting the drug, but subsequently dropped later on in comparison to the control group. Inversely, therapy causes the inflammatory condition that one is attempting to reduce. All parasites are impacted at the same time, which causes clinical deterioration that, if untreated with potent corticosteroids, could be fatal.

The best way to treat and/or prevent these adverse effects has never been thoroughly researched, despite the fact that they constitute a significant barrier to antiparasitic medication. There aren’t any controlled studies of corticosteroid treatment in the literature, despite the fact that virtually every conceivable regimen, duration, dose, or specific corticosteroid drug has been utilized to treat live brain cysticercosis cysts.

Conclusion

Until this point in time, a sum of 20 cases of SAH associated with NCC was found in the published literature (twelve of them corresponded to ASAHNCC). As we have established subarachnoid cysticercosis has been associated with the development of cerebrovascular events. The etiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage in neurocysticercosis remains unknown due to limitation on availability of causes related to it. Most cases (65%) of SAH associated with NCC improved (75% among cases of aneurysmal SAH) with medical and/or surgical therapy. The relation between NCC and stroke is deeply grounded.

NCC should be viewed as a differential diagnosis of stroke for younger and middle-aged patients especially if they do not exhibit conventional cardiovascular risk factors and come from endemic areas for cysticercosis.

NCC because of its individual characteristics requires personalized plan of treatment, there is not exact protocol with strong clinical evidence which medications or operative treatment should be used, but regarding existing practice there is established recommendations which should be used for better outcomes and not progressing disease or not getting lethal results.

Acknowledgement

We express our thanks to our paper mentor Dr. Koka Gogichashvili, Neurosurgeon in Caucasus Medical Center, Lecturer in New Vision University, for his support and encouragement all the time. Of course, big thanks to all of the authors of the paper, who spend a lot of energy and time. Special thanks to one of our authors Harshal Praveen Singh who found that brilliant case in Mumbai, India, Powai Polyclinic and Hospital.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

References

- Ravi Rajmohana, Dai Nguyenb, Noel Minerc, Steven Parkd, Hermelinda Abcedea, et al. (2022) Possible synergism of tissue plasminogen activator and neurocysticercosis leading to intracranial hemorrhage. Brain Hemorrhages.

- In Young Kim, Tae Sun Kim, Je Hyuk Lee, Min Cheol Lee, Jung Kil Lee, et al. (2005) Inflammatory aneurysm due to neurocysticercosis. J Clin Neurosci 12(5): 585-588.

- George M Viola, A Clinton White Jr, Jose A. Serpa (2011) Hemorrhagic Cerebrovascular Events and Neurocysticercosis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg 84(3): 402-405.

- Edinson Dante Meregildo Rodriguez (2020) Multiple neurocysticercosis and aneurismal subarachnoid hemorrhage: case presentation and systematic literature review.

- Khanal N, Shrestha R (2019) Seizure commonly associated with Neurocysticercosis are not linked with pork meat diet. A retrospective analysis. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences 10(5): 63-67.

- Liu T, Wang T, Bao Y, Jinghua Du, Yongchang Guan, et al. (2021) Cerebral cysticercosis mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. Chin Neurosurg J 7(1): 39.

- Cárdenas Graciela, Guevara-Silva Erik, Fleury Agnes, Sciutto Edda, Jose Luis, et al. (2012) Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Neurocysticercosis a Direct or Serendipitous Association? Neurologist 18(5): 324-328.

- Paula Eboli, Doniel Drazin (2012) Ruptured Aneurysmal Neurocysticercosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature.

- Svetlana Agapejev, João Luiz Parra-Marinello, Rodrigo Bazan, Anete Kinumi Ueda, Marco Antonio Zanini (2011) "Aneurysm and Neurocysticercosis: Casual or Causal Relationship? Case Report and Review of the Literature", Case Reports in Medicine p. 4.

- Eduardo Vieira, Igor V Faquini, Jose L Silva Jr, Maria F L Griz, Auricélio B Cezar Jr, et al. (2019) Subarachnoid neurocysticercosis and an intracranial infectious aneurysm: case report. Neurosurg Focus 47(2): E16.

- Meregildo ED (2020) Multiple neurocysticercosis and aneurismal subarachnoid hemorrhage: case presentation and systematic literature review. Infez Med 28(2): 268-272.

- F Alarcón, F Hidalgo, J Moncayo, I Vinan, G Dueñas, et al. (1992) Cerebral cysticercosis and stroke Stroke 23 (2): 224-228.

- H H Garcia, O H Del Brutto, T E Nash, A C White Jr, V C Tsang, et al. (2005) New concepts in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis (Taenia solium). Am J Trop Med Hyg 72(1): 3-9.

- IY Kim, T S Kim, J H Lee, M C Lee, J K Lee, et al. (2005) Inflammatory aneurysm due to neurocysticercosis, J Clin Neurosci 12 (5): 585-588.

- Laranjo González M, Devleesschauwer B, Trevisan C, Alberto Allepuz, Smaragda Sotiraki, et al. (2017) Epidemiology of taeniosis/cysticercosis in Europe, a systematic review: Western Europe. Parasites Vectors 10(1): 349.

- Eric T Kimura Hayama, Jesús A Higuera, Roberto Corona Cedillo, Laura Chávez Macías, Anamari Perochena, et al. (2010) Neurocysticercosis: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics 30(6): 1705-1719.

- Viola GM, White AC J, Serpa JA (2011) Hemorrhagic Cerebrovascular Events and Neurocysticercosis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 84(3): 402-405.

- Chun JY, Smith W, Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Wilson CB, et al. (2001) Current multimodality management of infectious intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 48(6): 1203-1213.

- Zee CS, Segall HD, Miller C, Tsai FY, Teal JS, et al. (1980) Unusual neuroradiological features of intracranial cysticercosis. Radiology 137(2): 397-407.

- Soto Hernandez JL, Gomez Llata Andrade S, Rojas Echeverri LA, Texeira F, Romero V, et al. (1996) Subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to a ruptured inflammatory aneurysm: a possible manifestation of neurocysticercosis: case report. Neurosurgery 38(1): 197-199.

- Huang PP, Choudhri HF, Jallo G, Miller DC (2000) Inflammatory aneurysm and neurocysticercosis: further evidence for a causal relationship? Case report. Neurosurgery 47(2): 466-467.

- Serpa JA, Yancey LS, White AC (2006) Advances in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 4(6): 1051-1061.

- Nash TE, Singh G, White AC, Rajshekhar V, Loeb JA, et al. (2006) Treatment of neurocysticercosis: current status and future research needs. Neurology 67(7): 1120-1127.

- Iwanowski L, Wisławski J (1987) Analiza neuropatologiczna 8 nie rozpoznanych przyzyciowo przypadków wagrzycy mózgu [Neuropathologic analysis of 8 undiagnosed cases of cerebral cysticercosis]. Neurol Neurochir Pol 21(4-5): 390-395.

- Sawhney IM, Singh G, Lekhra OP, Mathuriya SN, Parihar PS, et al. (1998) Uncommon presentations of neurocysticercosis. J Neurol Sci 154(1): 94-100.

- Barinagarrementeria F, Cantú C (1998) Frequency of cerebral arteritis in subarachnoid cysticercosis: an angiographic study. Stroke 29(1): 123-125.

- Rodriguez S, Dorny P, Tsang VC, Pretell EJ, Brandt J, et al. (2009) Detection of Taenia solium antigens and anti-T. solium antibodies in paired serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples from patients with intraparenchymal or extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis. J Infect Dis 199(9): 1345-1352.

- Bisdas T, Teebken OE (2011) Mycotic or infected aneurysm? Time to change the term. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 41(4): 570.

- Braga F, Rocha AJ, Gomes HR, Filho GH, Silva CJ, et al. (2004) Noninvasive MR cisternography with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and 100% supplemental O (2) in the evaluation of neurocysticercosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25(2): 195-197.

- Fleury A, Carrillo-Mezo R, Flisser A, Sciutto E, Corona T, et al. (2011) Subarachnoid basal neurocysticercosis: a focus on the most severe form of the disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 9(1): 123-133.

- Chavarría A, Fleury A, García E, Márquez C, Fragoso G, et al. (2005) Relationship between the clinical heterogeneity of neurocysticercosis and the immune-inflammatory profiles. Clin Immunol 116(3): 271-278.

-

Mirza Khinikadze*, Koka Gogichashvili, Mariami Natsvlishvili, Tinatin Chkhartishvili, Aditi Pandey, Harshal Praveen Singh. Neurocysticercosis and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Correlations -Systemic Review and Case Report Article. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 13(1): 2022. ANN.MS.ID.000801.

-

Neurocysticercosis, Subarachnoid, Hemorrhage, Correlations, Central Nervous System, Polycystic Kidney Disease, Tumor Necrosis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.